How Much Revenue Have Tariffs on China Made for America?

Hint: it's not enough to cover the costs to the American economy

Welcome to our new OCPL Fellows Feature series, brought to you by our current cohort of talented researchers. These pieces explore key challenges at the intersection of U.S.-China and global emerging technology competition.

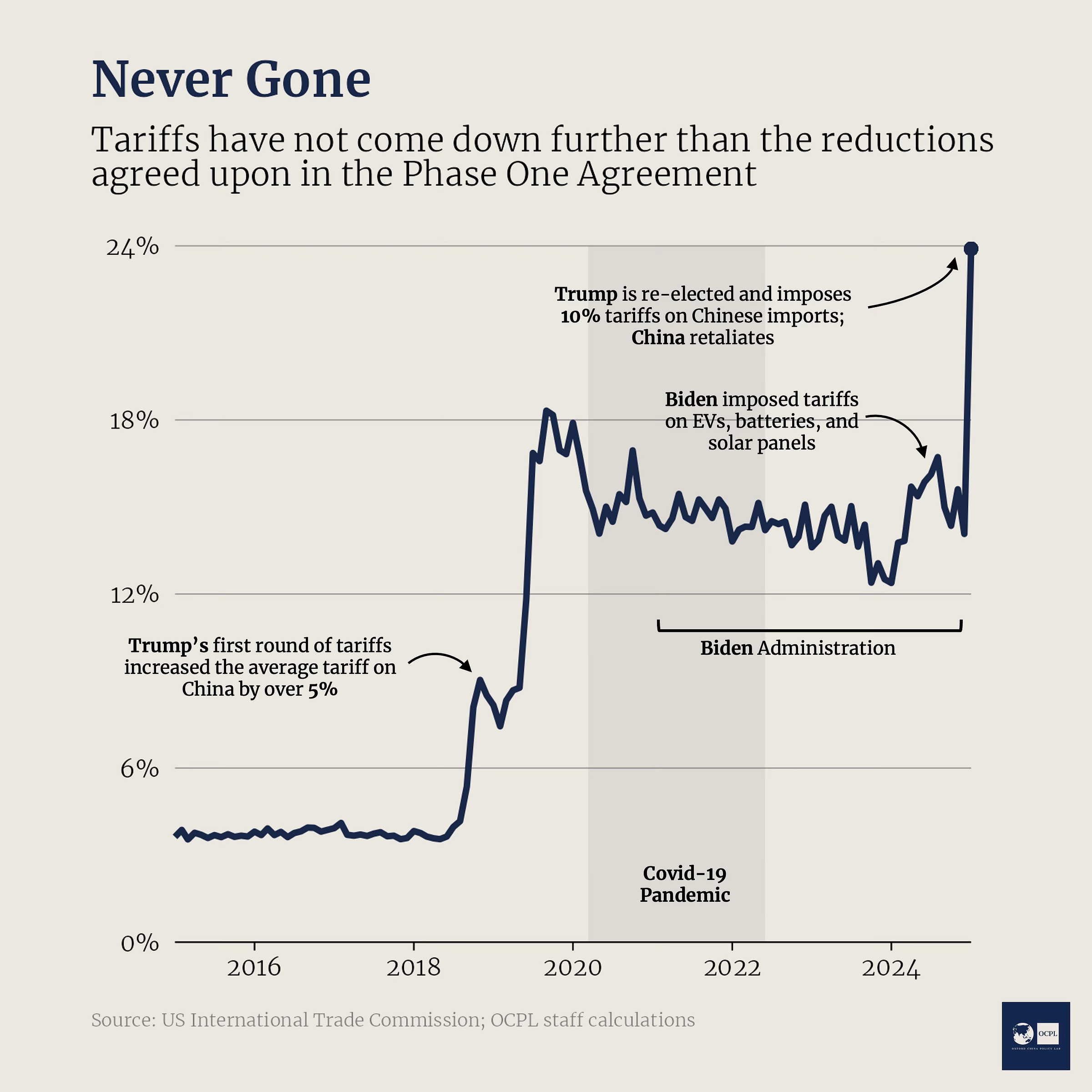

In February 2025, President Donald Trump made good on his campaign promise to renew tariffs on China. But were they ever gone? From 2018 to 2020, under the first Trump Administration, the United States increased the effective average tariff rate (the tariff rate averaged across types of goods) on China from about 4% to 18% amid a very costly trade war. In 2020, the United States and China made a ‘deal’ to end the trade war—the Phase One Agreement—which stipulated that some of the tariff restrictions would be removed alongside several trade and non-trade concessions. In total, the provisions in the agreement reduced the effective average U.S. tariff on China by about 3%.

After an interim four year period under the Biden Administration, the question stands: has there been any progress in returning the U.S.-China trade relationship to its pre-war status? Between 2021 and 2025, the average effective tariff on imports from China remained within a percentage point of 15%, despite hopes that the Biden Administration would continue tariff reductions. In September 2024, the Biden Administration even increased tariffs on China via a set of measures on imports of technologies including electric vehicles, batteries, and solar panels.

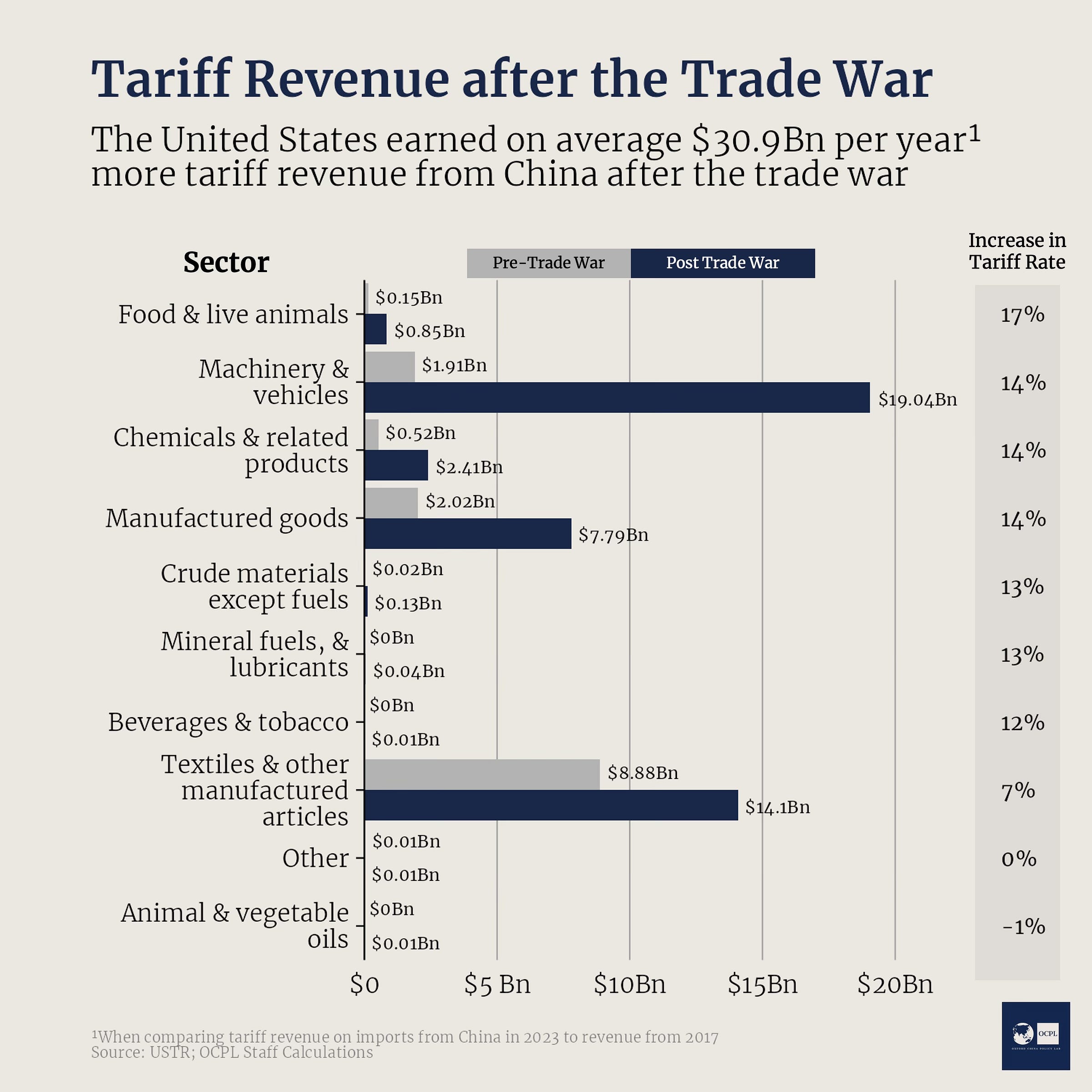

Tariffs on China incur a net cost for the average American. A 2019 report by the National Foundation for American Policy estimated that the first year of Trump’s tariffs cost the average American household an additional $657, for an aggregate total cost of $167.7 billion to the U.S. economy. During his 2024 presidential campaign, Trump suggested that foreign nations—namely China—pay for the cost of tariffs. He has argued that the losses caused by tariffs are more than made up for by the revenue that tariffs generate. Mr. Trump is not wrong in suggesting that tariffs generate substantial revenue for the United States—more revenue than the annual GDP of 86 nations—however, this revenue is still far less than the annual aggregate cost of the tariffs on the U.S. economy. In fact, since 2018, the trade war and subsequent tariffs have only generated $281 billion for the U.S. government, less than a quarter of the $1.2 trillion hole left by the trade restrictions. Overall, the net effects of the tariffs (the cost of tariffs minus the tariff income) cost the average American household over $352 per year.

In 2023, tariffs on China generated only $30 billion in revenue across all sectors of imports. Not all sectors are created equal, with the trade war targeting specific products, such as steel and advanced machinery. Of the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC)-prescribed 10 sectors of trade, machinery and vehicles saw the greatest increase in both the tariff rate and total tariff revenue, followed by manufactured goods and textiles. If China is the world’s factory, then the Trump and Biden Administrations have effectively taxed manufactured goods by between 7% and 14% since 2018.

The beginning of Trump’s second term has been characterized by brazen threats, and occasional use, of tariffs. With China, Canada, Mexico, and others firmly in the crosshairs of Trump’s next tariff moves, large swathes of America’s imports have already or may soon become subject to cost increases which the government will not be able to recoup through the revenue from tariffs alone. In the continued competition with China, tariffs are not the silver bullet that the Trump Administration wishes they were. When rolling out new tariff measures, U.S. policymakers should be careful not to shoot America in the foot.